THOMAS FISHER RARE BOOK LIBRARY

The Way To Their Heart is Through Their Stomach

Persuading British Immigrants to Settle in Upper Canada through Food in the Early 19th Century

[Maple] sugar, if refined by the usual process, may be made into as good single or double refined loaves, as ever were made of the sugar obtained from the juice of the West India cane.”[1]

“A Few Plain Directions” for Immigration

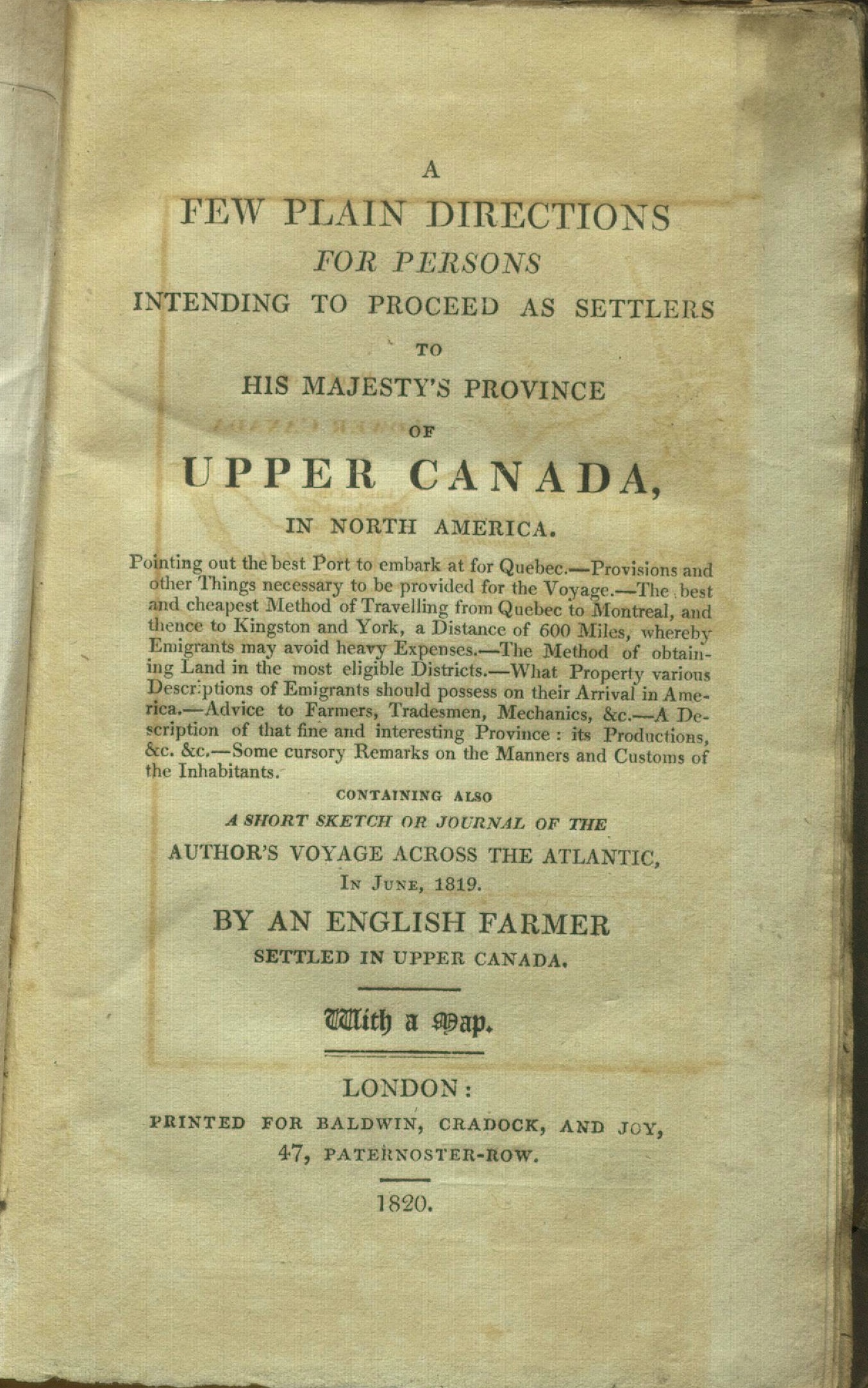

In the 19th century access to migration information was limited. Immigration guides were rich sources providing details about all aspects of settler life. This 1820 immigration guide[3] is both a guide and advertisement encouraging British citizens to immigrate to Upper Canada[4].[5] Six chapters provide information on the journey, directions and conditions upon arrival, best areas for settling, and established settler communities.

Courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

This is the inside title page of “A Few Plain Directions for Persons Intending to Proceed as Settler’s to His Majesty’s Province of Upper Canada.” It provides contextual information, outlining the immigration experiences it will describe. This display features “Chapter V: Animal and Vegetal Productions of Upper Canada.”

Chapter Five, “Animal and Vegetal Productions of Upper Canada,” explores Upper Canada’s natural resources and how they might be used, providing market prices for skins, meat, and crops and instructions for how to cook with them. The text emphasizes culinary similarities to Britain,[6] building connections between food in Upper Canada and home to communicate with, intrigue, and encourage potential migrants.

Immigration in 19th Century Upper Canada

There was a wave of British migration to Canada in the19th century, receiving almost one million settlers between 1815 and 1850.[7] British and Canadian officials had a hand in this, creating immigration guides to encourage British individuals to settle in particular areas of Canada.[8] This immigration guide acknowledges the increasing settler population, noting that the settler “sees around him the neat and convenient habitations of…settlers” with the “hand of industry…everywhere visible to him.”[9]

“Speaking” to Potential British Immigrants Through their Stomachs

I found myself grinning at the ways this chapter encourages immigration through food by emphasizing connections to home and evoking curiosity for the culinary uses of Canadian resources. Beavers’ tails (not the fried treat we know today), for example, are presented as a Canadian delicacy.[10] Some culinary connections between Upper Canada and Great Britain include: supplies of wild duck and pigeon; American partridge, with “particularly fine flavour, superior[…] to that of the English partridge and pheasant;”[11] Canadian hare, which are larger than English hare but tender;[12] and fruits, like cherries, plums, and cranberries that make delicious preserves and grow abundantly equal to English gardens.[13] It even provides recipes for maple tree sap, including: maple sugar “as good as West India cane;” Maple Beer, a “delicious and wholesome drink;” and Maple Wine “equal to wines imported from foreign countries.”[14]

“Speaking” to the Stomachs of Today

With almost half the population composed of immigrants, current day Toronto is rich in multiculturalism,[15] which is evident in its culturally diverse food scene. Moving to a foreign place elicits feelings of loss and longing for the comfort of home.[16] Thus, food associated with that feeling provides the possibility of comfort through memory, nostalgia, and the senses.[17] Integrating new ingredients and sharing these comfort foods can even help newcomers form attachments with their new setting.[18]

In 2008, the Toronto Environmental Alliance[19] created four cultural food guides for the Greater Toronto Area, highlighting sources to buy locally grown ingredients for Chinese, South Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and Caribbean cuisine.[20]

Courtesy of Toronto Environmental Alliance.

This is the front cover of the African Caribbean Food Guide.[2] It provides resources for finding locally grown African Caribbean produce in Ontario to provide everyone the opportunity to make cultural and traditional foods.

They include lists and maps of retailers, farms, and farmers’ markets providing cultural ingredients.[20] These guides proclaim that everyone deserves fresh, locally grown food that tastes like home. While the larger context of today’s population is much different than that targeted in this 1820 immigration guide, the same impulse to reach for peoples’ sense of home through their stomachs underlies both worlds.

BIO

Sarah Kelly is a Graduate Student currently studying at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Information. She is working on completing two graduate degrees, a Master of Information, concentrating in Archives and Records Management, and a Master of Museum Studies. Her areas of interest include the convergence of archives and museums as well as archival and museological community outreach. Sarah earned a Bachelor of Arts in Honours History at the University of Guelph.

[1] https://archive.org/details/cihm_21084

[2] http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/upper-canada/

[3]Library and Archives Canada, 2006

[4]Library and Archives Canada, 2006

[5]Harris, Matthews, and Gentilcore, 1987, p. 21

[6]Library and Archives Canada, 2006

[7]Chapter VI, 1820, p. 94

[8]Chapter V, 1820, p. 69

[9]Chapter V, 1820, p. 80

[10]Chapter V, 1820, p. 70

[11]Chapter V, 1820, p. 89-90

[12]Chapter V, 1820, p. 85-87

[13]Statistics Canada, 2011

[14]Lessa and Rocha, 2009, p. 150

[15]Lessa and Rocha, 2009, p. 150

[16]Lessa and Rocha, 2009, p. 153

[17]http://www.torontoenvironment.org/campaigns/greenbelting/foodguide/thefourguides

[18]Toronto Environmental Alliance, 2008

[19]http://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/toenviro/legacy_url/883/Afro_Caribbean.pdf?1419018085

[20]BlogTO, 2009

[21]Chapter V, 1820, p. 85

Moving to a foreign place elicits feelings of loss and longing for the comfort of home.[16]